Blogroll

- Meals I Have Eaten

- Jess's New Blog

- One of Jess's Old Blogs

- The Stop Button

- Jenerator's Rant

- The Rejection Collection

- Pockets Stuffed With Notes

- The Silkie Road

- PostSecret

- Informed Comment

- Talking Points Memo

- Spoken & Heard

- Ever So Strange

- that-unsound

- Marvelous Prompts (& Responses)

- Only Words To Play

- So Misunderstood

- Acknowledge & Proceed

Profile & Email

Previous Posts

- never paralyzed

- ...the nostalgia

- foursets (revisionato)

- is it just me...

- what blows away finds its web

- fester

- lines and subways and lines

- more fictation: Swallow

- coaster lovin'

- two words only

Archives

- April 2005

- May 2005

- June 2005

- July 2005

- August 2005

- September 2005

- October 2005

- November 2005

- December 2005

- January 2006

- February 2006

- March 2006

- April 2006

- May 2006

- June 2006

- July 2006

- August 2006

- September 2006

- October 2006

- November 2006

- December 2006

- January 2007

- February 2007

- March 2007

- April 2007

- May 2007

- June 2007

- July 2007

- August 2007

- September 2007

- October 2007

- November 2007

- December 2007

- January 2008

- February 2008

- March 2008

- April 2008

- May 2008

- June 2008

- July 2008

- August 2008

- September 2008

- October 2008

- November 2008

- December 2008

- January 2009

- February 2009

- March 2009

- April 2009

- May 2009

- June 2009

- July 2009

- August 2009

- September 2009

- October 2009

- November 2009

- December 2009

- January 2010

- February 2010

- March 2010

- April 2010

- May 2010

- June 2010

- July 2010

- August 2010

- September 2010

- October 2010

- November 2010

- December 2010

- January 2011

- February 2011

- March 2011

- April 2011

- May 2011

- June 2011

- July 2011

- August 2011

- September 2011

- October 2011

- November 2011

- December 2011

- January 2012

- February 2012

- March 2012

- April 2012

- May 2012

- June 2012

- July 2012

- August 2012

- September 2012

- October 2012

- November 2012

- January 2013

- March 2013

- May 2014

n. infantile pattern of suckle-swallow movement in which the tongue is placed between incisor teeth or between alveolar ridges during initial stage of swallowing (if persistent can lead to various dental abnormalities) v. [content removed due to Bush campaign to clean up the internet] n. act of nyah-nyah v. pursuing with relentless abandon the need to masticate and thrust the world into every bodily incarnation in order to transform it, via the act of salivation, into nutritive agency

Tuesday, March 14, 2006

enamorada

My dears, this is a work in progress, especially so...

My dears, this is a work in progress, especially so...Motion at the Margins

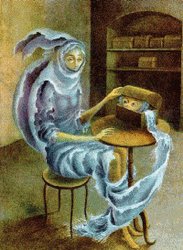

An essay on Remedios Varo should not begin with biographical information. Varo's works speak for her selves, and I think she'd agree. It is not the movement of the individual through a tangible place in history that makes a work reverberate, but what we can find within. Here’s what I see: creation, metafiction, solitude, reworked myth, isolation, play, female, locomotion, landscape, science rethought.

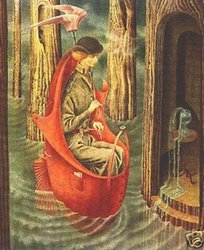

To start. Next door in image 2 and below in image 3, we see two examples of what intrigues me about Varo: her characters are solitudes, and rarely do two solitudes meet. The painting with a man riding a wheel (Vagabond), and the painting of a woman in a boat (Exploration of the Sources of the Orinoco River) speak to the motion of the individual through space. Both of these characters are inventive, and not only that, they invite dialogue.

To start. Next door in image 2 and below in image 3, we see two examples of what intrigues me about Varo: her characters are solitudes, and rarely do two solitudes meet. The painting with a man riding a wheel (Vagabond), and the painting of a woman in a boat (Exploration of the Sources of the Orinoco River) speak to the motion of the individual through space. Both of these characters are inventive, and not only that, they invite dialogue. The vagabond moves himself through a forest on a windblown vehicle. It is not sufficient for the vagabond to simply walk; rather, he has incorporated his body into a contraption that turns and turns. It is through the cyclical motion of the wheels – objects that suggests continuity, revolution, and energy – that the vagabond makes his way in the world. He does not simply lift his feet in a series of cause-effect motions that would suggest disconnected serial progression, but instead he spins along, carefully balanced on two single and disconnected rotations. And instead of being propelled by an inexplicable gas engine, his wheels are connected to two wind turbines above the man’s head. One might wonder where the wind is coming from, based on the closeness of the forest around him, but regardless our vagabond is at the edge of the path, and so he has made it somewhere, and with the energy he can find along the way.

We cannot see what directions the vagabond is spinning towards, but we can see the past. The past is suggested by a path cut through an organic landscape, and it is also suggested by what the vagabond carries with him: a picture, books on a bookshelf, a cat near his feet, a flowerpot and pan near his heart. His head is encased in a roofed dome with two windows, and were he to choose, the vagabond could close himself in with his personal past - shut himself off to the path behind and the path in front, which demonstrates to me the division between personal and traveled path and the sealed space within which we exist and yet still move.

Likewise, this woman in the boat controls her vehicle with devices sprung from her body. Unlike the vagabond, she carries nothing but the means to motion. Unlike the vagabond, her motion is a search for something. There is something nostalgic and backwards looking about the vagabond, whereas the woman is looking forward. And for what does she look? For “the sources,” or what looks like a glass spring housed in carved out tree. The “source” sits on the top of a glass table, and is a combination of organic (water/tree) and inorganic (manmade creations). But no matter what, our intrepid female traveler is going to fuel her wings with her hands, her body, her clothes, and give wing to her desire to find some form of truth.

Likewise, this woman in the boat controls her vehicle with devices sprung from her body. Unlike the vagabond, she carries nothing but the means to motion. Unlike the vagabond, her motion is a search for something. There is something nostalgic and backwards looking about the vagabond, whereas the woman is looking forward. And for what does she look? For “the sources,” or what looks like a glass spring housed in carved out tree. The “source” sits on the top of a glass table, and is a combination of organic (water/tree) and inorganic (manmade creations). But no matter what, our intrepid female traveler is going to fuel her wings with her hands, her body, her clothes, and give wing to her desire to find some form of truth.Note the narrative one can give to these pieces (and we could keep going). This is what I mean by "inviting dialogue." These pieces suggest a story and a motion through space. And it is a motion that we get to fill in as we look for the myth that moves these rather fantastical pieces.

When I first looked at some of her paintings, I thought that Varo was perhaps a little too fantastic. In a world of disease, war, poverty, etc., how dare she painting “darling” little fairy tales! But I changed my mind. Varo’s paintings are lonely and inventive, and they demand that we acknowledge the loneliness and yet connect to it. The external is connected to the internal - physically, unapologetically. But the processes by which these two characters are moving are unique, and I found myself asking questions like:

If we are isolated, how will you tell a story? If we are static beings of flesh, how will we invent a new means of moving? Where are we going to go? What are we looking for? What materials can we use to get there?

These questions need some biography, (although I can't yet articulate why).

Varo was born in, and grew up in Spain. She was early interested in art, and drew pictures of fairy tales even as a child. Her father, supportive of her interest, scrapped together enough money and sent her to art school after a series of Catholic schools that would later show up in her work. At art school, she chafed at the edges, but explored fairly classical forms.

In order to finally escape, Varo married another artist and moved to Barcelona. In Barcelona, she entered some surrealist groups, but the main surrealist movement was taking place in Paris. In bold verbosity, she wrote off to the surrealists and told them of her commiseration with their aesthetic goals. Eventually, one of the surrealist bigwigs--Peret--came down and met with her along his journey.

Yeah, and love was to be had. Which is interesting. Varo had a number of lovers, and if you remember, was married, but she still managed to stay friends with them all and they hung out with each other. Something I would have liked to have seen. (How is this possible? I still want to knock my ex’s head off for sleeping with my friend after ditching me). This was all happening right around the time of the Spanish Civil War. Varo’s younger brother got himself killed on the Franco side of affairs, and Varo’s decision to leave her husband and join Peret in Paris might have been influenced by the increasing random violence that was occurring around her.

Her move probably was a wise choice, since she later had to rescue her Spanish husband from an internment camp, but once she had left, she was branded a leftist artist and barred re-entry into Spain. This is where her voyage started, and much of her most impressive artwork seems to point towards a longing to find home, an eternal sense of displacement, and the “vagabond” lifestyle that left her without a center to her multiple identities.

I relate, to say the least.

[Alright, I’m stopping here for now. I’ll come back.]

----

all bio info, and some dialogue on Varo’s works, from:

Kaplan, Janet. Remedio Varo: Unexpected Journeys. NY: Cross River Press, 1988.

images nabbed from various internet spots, but they’re Varo’s.

Comments:

Home

yes, that was nice. i called my best buddy after reading about Varo and told her that we needed to start cooking, and building new worlds, and she should be closer, and i missed her, and all of that... their friendship made me long for some kind of future. anyhow, i have to finish/rewrite this piece; i have a new idea for where i want it to go, i think.

Post a Comment

Home